Side Trip to Chickaloon Coal Mine

The Alaska Journal

Christine M. Ayars

Autumn 1977

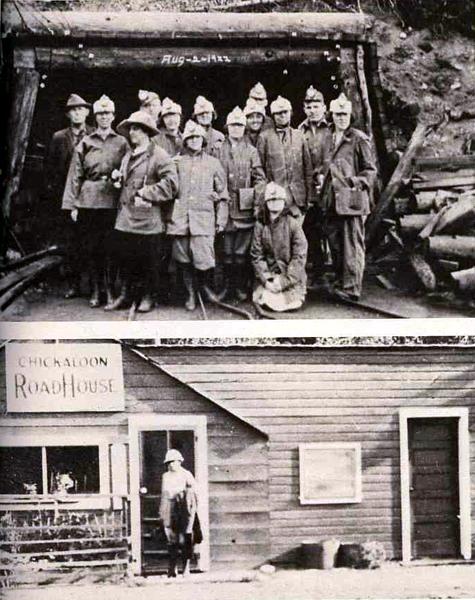

A tour of the Chickaloon Coal Mine in 1922 attended by Col. Mears submitted

by Pat Durand. Of the article, Pat says, "Miss Christine M. Ayars toured

Alaska via the Alaska Steam Ship Line and the Alaska Railroad in 1922. The Inkowa

Outdoor Club of New York City was dedicated to providing outdoor activites for

its city-dwelling young buisnesswomen members and thus sponsored this trip.

Miss Ayars wrote and photographed the images for her 11 page article, THE ALASKA

TOUR, 1922, which appeared in the Autum 1977 issue of The Alaska Journal on

pages 227 -237. The Chickaloon Coal Mine branch was abandoned beyond Eska in

1928. Miss Ayars' account of the group's side trip gives the flavor of the

place and time long past. I've copied that portion of her story as it relates

to the Alaska Railroad and offer it here for historical perspective."

We left the train at Matanuska to change

for one bound for Chickaloon. This train had stopped to let the trainsmen eat

lunch and add a lot of empty freight cars. While waiting we wandered down the

main street toward a barn. A gentleman there, who owned several cows, presented

each of us with a nice drink of fresh milk, then a real treat in Alaska. The

stationmaster showed us a birch basket full of fine-looking strawberries that

had been grown nearby. A private car at the end of the train was reserved for

Colonel F. Mears, the engineer builder of the Alaska Railroad. Presently Mrs.

Mears invited all of us to their car. At Moose Creek we all got out and ate

a delicious lunch.

Another stop was made at Sutton, where

we were given an escorted tour through the U.S. Navy's coalwashing plant. The

men in charge were feeling very provoked because Congress had failed to provide

the funds needed to continue to run it. It had cost about $450,000 to build.

What annoyed the men most was that no attention had been paid to the fact that

the Chickaloon Mine's coal produced much better heat to the ton than the best

U.S. coal from Pocahontas, Virginia.

Meanwhile, Colonel Mears's gas speeder

had caught up with us. It was a Ford car from which the tires had been removed

so the wheels could run on the rails. It had a front similar to a train engine's

cow catcher fender and the seats ran lengthwise. We were invited to ride in

it while the Colonel and a Mr. Gerry sat at the ends making notes of any places

where the Matanuska River had torn away or otherwise undermined the bank that

supported the tracks. At Mile 30, a place called "Hole in the Wall"

on account of previous ravages of the river, it was suggested that we go berrying.

Unfortunately, there were few ripe raspberries or highbush cranberries to reward

our efforts. The car rattled along between the Chugach Mountain making some

gasoline smell, but the view was gorgeous. Then around a bend appeared the Chickaloon

Valley with impressive Castle Mountain.

We barely had time to wash up for supper,

which was a real feast with bee, potatoes, string beans, a tomato and lettuce

salad, cranberry jelly, tea or coffee, peaches and delicate cake with frosting.

Immediately after that we walked to a Mrs. Dowling's house to enjoy the scenic

panorama which its high elevation and isolation offered. Sadly, former occupants

had left it in a rather messy condition.

Well fortified by our abundant and delicious

supper we next set out for the Chickaloon mine office. There we were outfitted

with new blue denim miners' caps and jackets. Since my jacket had only a handkerchief

pocket, my battery was strapped on by a belt. The cable car was a sort of open

box with shelves upon which we sat, clutching them tightly lest we fall out.

Newspapers had been spread over the shelves to try to keep a little of the coal

dust off our clothes. The only light during our 500-foot descent came from our

headlights. These made weirdly uncertain, changing shapes and shadows of our

surroundings as our cable car was lowered. Even though this was done much more

slowly for us than for the miners, we were nearly bounced off backward by the

sudden stop at the bottom. Those of us in the first party down noted that the

face of the second group were drawn and white from freight as they landed after

the ghostly ride. We then discovered that our car seats had decorated the rear

of our light-colored linen knickers with large, dark spots. It was wet underfoot

as we walked along the passage where upright logs had been put in every few

feet to shore up the rock walls. We followed a coal vein to the last blasting

area, where we found that side walls had been set up. Opposite this area was

a shaft with a skip in it to carry the newly blasted coal on a track to the

chute to be dumped into cars in the main passage. Whenever work was begun on

a parallel lower level, a chute was blasted twenty to thirty feet down to that

level to form an air chamber and make a current of air. The pillars in the upper

passage were quite large at first, but were gradually blasted off to the smallest

size that would provide safe supports. Coming up in the cable car was easier

than the descent.

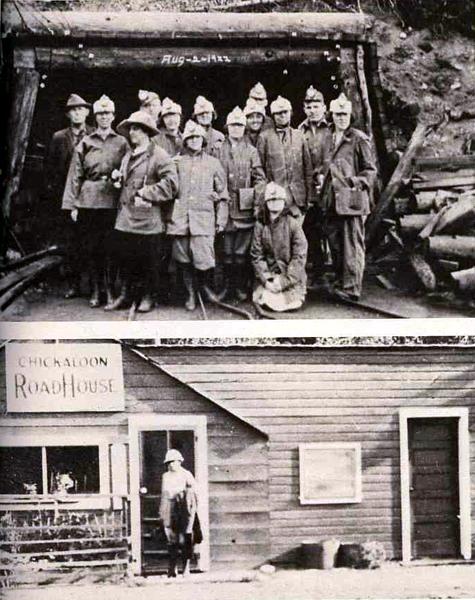

The Chickaloon Road House manager had been

informed of our arrival ahead of time. So provision had been made for the men

who had come on the same train as we to sleep elsewhere. Upon entering the roadhouse,

we first came to one small room containing a double-decker, fully equipped with

bedding, including white bedspreads. In the main room however, the five two-deckers

had but one sheet for each bunk. We did not know whether to sleep on top of

or under the sheet, so we wore our nightdresses over our underwear. Despite

the heavy blankets and a comforter it was so cold at night, with a door partially

open, that I also put my coat on for warmth. Just one centrally located electric

light bulb furnished all the light. The washing facility consisted of a long,

narrow wooden trough with three basins, each inserted in a hole through which

the used water could be poured into a pail standing on the floor below. Outdoors

was a privy at a little distance. This did not appeal to us for winter use,

when the temperature would be many degrees below zero.

We had a fine breakfast and then took turns

riding in the train's caboose back to Sutton. The conductor pointed out Eska

Mountain, with snow in some crevasses, the lovely blue-green of Eska River and

the best camp for the railroad workers that the Government Commission had ever

built.

|

Top - Inkowa Outdoor Club members

(includes author) in miners' jackets and caps preparing for the descent

into the Chickaloon Mine. Although cool was reported in the Chickaloon

area as early as 1899 and a sample of 800 tons from the area tested by

the Navy in 1914, it was not until after completion of the Matanuska Branch

of the railroad to Chickaloon in October of 1917 that the coal was shipped

to market. The coal was mined by the Alaska Engineering Commission under

contract to the U.S. Navy. Shortly after the author's visit the mines

were closed as a result of the Navy's decision to convert its ships from

coal to oil-fire boilers.

Above - Chickaloon Road House.

|

BACK