colossal scale. Taming this wilderness requires a great deal of innovation as well as perseverance. In the 1970s, it was the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System carrying oil 800 miles from the North Slope of Alaska to the ice-free port of Valdez, Alaska. In the early forties it was the 1,523 mile narrow, winding dirt road dubbed the "Alcan Highway." But before all this was the "Loop", famous for its solution in building the railway through an exceptionally steep section of the mountains.

Loop Construction

Virtually

no records exist describing the actual construction of the Loop itself.

We do know that the elevation gain in the region was too steep a grade

for steam powered trains. At some point, the builders of the railroad

realized a pig tail loop would provide the necessary grade required.

Construction would have been most difficult. Workers had to contend

with dense alders, mosquitoes, moose, bear, avalanches, heavy snowfalls

and blizzards. Their efforts yielded an engineering marvel as well

as something scenically spectacular.

Virtually

no records exist describing the actual construction of the Loop itself.

We do know that the elevation gain in the region was too steep a grade

for steam powered trains. At some point, the builders of the railroad

realized a pig tail loop would provide the necessary grade required.

Construction would have been most difficult. Workers had to contend

with dense alders, mosquitoes, moose, bear, avalanches, heavy snowfalls

and blizzards. Their efforts yielded an engineering marvel as well

as something scenically spectacular.

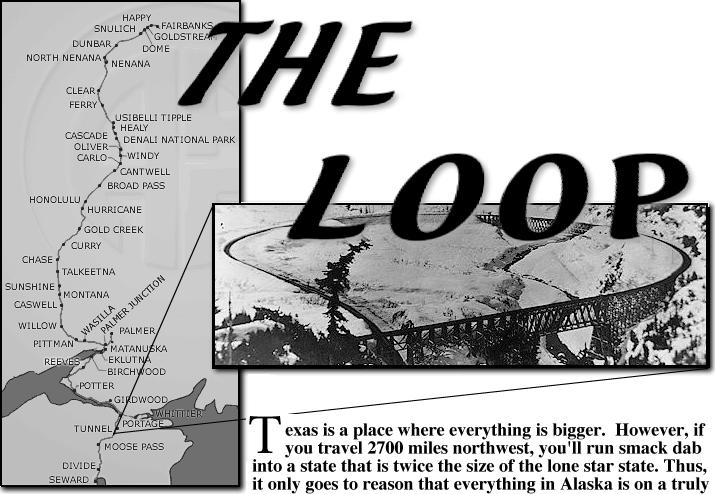

In Bernadine Prince's book, The Alaska Railroad states, "A little north of Mile 48 the line passes through a tunnel of a distance of 714 feet, turning to the right on a 14 degree curve, with a total curvature of 235 degrees. Much of this turn is made on a trestle whose maximum height is 106 feet. The line continues to descend on the maximum grade, crossing various high points to Mile 54, where the foot of the heavy grade is reached. In Miles 50 and 51 a complete loop is made, the road crossing under itself."

Loop Elimination

Over the next three decades, Bartlett Glacier receded

significantly, thus making it possible to eliminate the Loop. The

railroad could now develop grade line on fill rather than depend on wooden

structures. Although the Loop had served its purpose well, there

were many advantages to removing it.

At a cost of approximately $36,000 a year, the Loop was expensive to maintain. A new route would eliminate repairs to five Loop bridges, a snow shed and one tunnel. It would no longer be necessary to maintain a heating plant and two watchmen at the tunnel. It would also take the mainline away from a treacherous snow slide area. A new route would also permit the railroad to use its heavier diesel electric F7 1500 series units instead of lighter steam locomotives. The Army also had an interest in eliminating the Loop since they felt it was very vulnerable to sabotage. But perhaps the biggest benefit of removal was getting rid of a collection of untreated, deteriorating lumber that was slowly becoming structurally unsound. As resident engineer Cliff Fugelstaad remembers it, "The trestles were getting pretty shaky. We breathed a sigh of relief when we got off of them."

Cliff began working the line change in late 1950. Surveying was done in the winter and deep trenches were dug into the snow so the survey transits could set on the ground. Once the snow melted, the work began in earnest. The new alignment required lots of rock work, blasting and one high fill. "There wasn't lots of sophisticated equipment then. We used some hydraulic jacks. All tamping was by hand. We had twenty to thirty men tamping ballast. Once you start grade work, you have to finish [without quitting.]"

With winter on their heels, the workers pushed on fiercely. "There was one close call on lining over the old to the new. October was very cold and the ground was freezing. Also, the ballast or gravel loaded in rail cars would freeze in and there would be a heck of a time dumping it. However, my boss, Anton Anderson, assured us, 'Don't worry. There will be a thaw equal in length to the first frost.' And he was right. We got a thawing spell in the first two weeks in November."

Finally, on November 6, 1951 the line change was opened

and the famous Loop District between miles 47.5 and 50.8 was eliminated.

A total of 1.1 miles was cut off the Seward to Anchorage run, costing the

railroad $1,000.000. General Manager J.P. Johnson dove a golden spike

marking the completion of the line.  As

Bernadine Prince states in her book, The Alaska Railroad, "The last

rail was dropped into place at 11:06 a.m. and the final spike was driven

by Colonel Johnson at approximately 11:30 a.m. Work cranes, gas cars

and other equipment were shifted out of the way as freight train No. 32

and Anchorage-bound freight out of Seward, started down the new three percent

grade from Grandview at 1:30 p.m. behind three puffing steam locomotives."

As

Bernadine Prince states in her book, The Alaska Railroad, "The last

rail was dropped into place at 11:06 a.m. and the final spike was driven

by Colonel Johnson at approximately 11:30 a.m. Work cranes, gas cars

and other equipment were shifted out of the way as freight train No. 32

and Anchorage-bound freight out of Seward, started down the new three percent

grade from Grandview at 1:30 p.m. behind three puffing steam locomotives."

It was later decided that all unused trestles should be torn down as a safety precaution. The railroad asked for bids from the private sector and a contractor selected. Cliff states, "The company scalped the good stuff and left the junk. The railroad had to go back in later and bring it down."

Alaska Railroad employee Charlie Rainwater adds, "The reason they wanted it down is because the tourists would get up there and walk out and take pictures. The liability became too great. They decided they better get the thing down. There was 'No Trespassing' signs, but that don't mean anything. So they let a contract to have it destroyed. The contractor was to salvage any part he wanted from it, but then had to get the rest of it on the ground. Well, the contractor took the choice pieces out of it and then pulled out of the job. He had a $2,500 surety bond and that meant nothing." Charlie was put in charge of removing the old trestle. He recalls being told, "Charlie, go down there and get it on the ground."

Now began the daunting task of destroyed the Loop. Charlie explains, "The Superintendent of the off track equipment was with Patton's army and he told me that all I had to do was get some primer cord and wrap it around those pilings and set it off. That will cut those pilings in two and that bridge will come right down." The Army offered use of its primer cord stock to help bring down the timbers. Charlie went out to the base, retrieved multiple spools of primer cord and was told to wrap several loops of it around each piling. Wanting to do the job right the first time, Charlie and the section crew spent two days putting five wraps around each and every piling. He then hooked the primer cord to a magneto plunger, push down the handle and set it off. "Man there was an awful amount of dust and smoke and debris flying everywhere. I went down to take a look and it didn't even take the black off of some of those pilings. It didn't do anything to it, just scratched it. All that was for nothing. I found out later that primer cord was used to set off other explosives. It ended up we had to take chain saws and saw chunks out of the pilings on the down stream side. Then we hooked a D8 Cat and a long cable to it and put him downstream to pull. He couldn't budge it! So we had to go in and cut all the way back past the center pile and finally the whole thing come over and then burned it up. It took the better part of two weeks to do the job." [Also see Excerpts from Charlie Rainwater's Memoirs]

The Loop Revisited

I made two visits to the old Loop District in 2002 in

which I searched for remnants of this historic landmark. The first

was a Hi-rail excursion with Frank Dewey and company on July 25 while the

other was a flight seeing trip with Jim Somerville on August 4. I

was armed with engineering drawings from the Alaska

Railroad showing both the old and new mainline.

The most precise way to ferret out loop leftovers is on foot. The easiest way is from the safety of a Hi-rail. Since the alders were as thick as steel wool and the mosquitoes were swarming relentlessly, I chose the later. We spotted many instances of ridge lines of stubby vegetation which represented the old rail grade. As an added bonus, we found timbers from the old trestle and concrete abutments from the pilings. If I ever make a return trip on foot, I will set aside an entire day and come armed with a machete for it would be quite a rush to follow the old grade through the entire Loop District. These efforts would be rewarded with views of an old snow shed, tunnel and abandoned box car.

|

|

|

| Old grade and parts of the old trestle | Close up an old trestle support | Concrete piling trestle support |

The Hi-rail run was fun, but the aerial view from Jim Somerville's airplane provided me with an awesome view and better understanding of the old Loop District. What I once saw as missing ridges of vegetation during the Hi-rail trip now appeared as old cuts still filled with ballast. The highlight was viewing the actual loop grade itself, tracing it from its point of origin, through the pig tail and out as it headed to the foot of a nearby mountain.

|

|

| New and old grade side by side | Remnants of the old Loop itself |

Bonus photographs

On 3/3/16 Charles Ek added:

In 1907, William G. Atwood, the Alaska Central Railway's Assistant Engineer of Construction, published a detailed article in "Engineering News" titled "Construction of the Alaska Central Railway, with Cost Data." In that article he described the construction of the Loop District. Of particular interest to me is his specification of the trestles' round poles, hewed mud sills, other sawn timber and their dimensions, as well as the unusual span distance of 20 feet. There's also a photograph of the trestle being constructed at mile 48. Click here to see the article.

Page was created on 9/20/02 and last updated 11/13/19